Drilling in the sea is more complicated than on land; the lack of stability (for floaters), the corrosive environment, the more cramped conditions and the more difficult support logistics all dictate this.

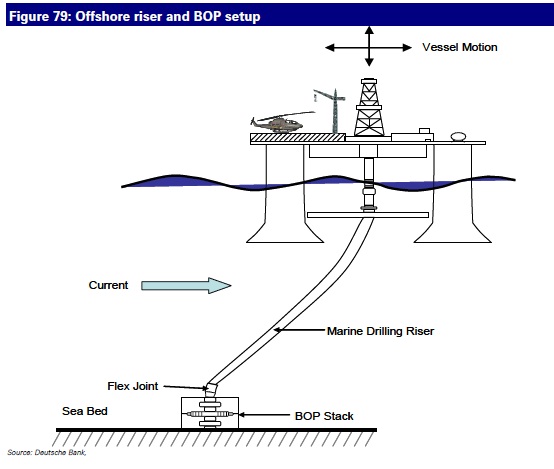

During drilling the offshore well needs to be extended from the seabed to the rig floor, so that the mud system can be controlled. This is achieved by using a ‘riser’, which is a large diameter steel pipe that connects the top of the well on the seabed with the rig. The BOP can either be mounted on the seabed or be on top of the riser at the surface. Rigging up and down the riser for each well adds on to required rig time versus an onshore operation, and pressure testing the entire system is also more complicated than onshore BOP pressure testing.

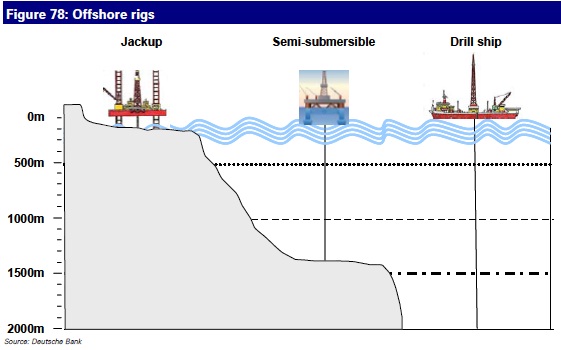

Within offshore rigs there are two main categories; jackups and floaters. Jackups do not float, they simply stand on retractable legs (usually three) and hence provide a stable platform from which to drill.

The Jackup can of course only work in water depths that are less than the length of its legs, and typically this limits operations to less than 400ft water depth. When moving between drilling locations the hull is usually towed by tugs or carried by a specialist vessel, with the legs sticking high into the air. Once the jackup has arrived at the drilling location, the legs are lowered to the seabed, and then the hull (upon which all the drilling equipment is installed) is jacked up the legs, so raising itself out of the water.

Unlike Jackups, floaters are not limited to 400ft water depths as they do not rely on standing on long legs. They are essentially ships with drilling equipment, are usually self propelled and have a marine crew. When it arrives on location the floating rig needs to anchor with the help of support vessels, which can be a time-consuming process, but the main technical challenges versus jackups is the floating nature of the platform. The problem is that the rig will move up and down with swell and with tides if present, but the well bore of course doesn’t i.e. the drill pipe will have a tendency to smash into the bottom of the hole simply with the heave of the rig, which would make drilling a decent well problematic. The solution involves using a large hydraulic system known as a wave-motion-compensator. It adds up to yet more mechanical systems to operate, maintain, and potentially go wrong.

Drillship or semisub? Which of a drillship or semi-submersible is better is unclear, and basically seems to come down to availability as much as technical factors. It could be argued that transit speed between locations is faster for drillships and that keeping on station (whether by anchors or dynamic positioning) is easier in certain prevailing current locations with a long, thin ship-shape than a square semisub shaped hull. However the ship-shape layout limits space for an operation that uses ever larger equipment and ever more subcontractors (that all want a bed to sleep in and a doghouse for their specialist equipment).

Logistics and supply. There is an entire industry that simply services the logistical needs of the offshore drilling industry. It includes:

1) Catering – supply of food and onboard catering staff and cleaners

2) Supply vessels – to supply fuel, food, water, chemicals, drill pipe, casing, cement and act as an offshore storage facility when deck space becomes tight.

3) Supply vessels – used to act as emergency support for evacuation in bad weather or kick/blow-out scenarios, sometimes for transport of personnel from shore or from rig to rig within a field, and occasionally as accomodation if there’s no space left on the rig.

4) Anchoring vessels – usually supply boats or dedicated powerful tugs that aid in th elaying of anchors

5) Helicopters – the provision of helicopter transport and smergency support.